|

Manila This all was way back in the golden days when Goethe Institutes were still run by true characters with an insatiable thirst for experiments in culture. In Manila’s case, these portal figures were Gerrit Bretzler and Uwe Schmelter. Truly different personalities with different approaches but identical goals: infusing ideas, lending a helping hand, strengthening the young sprout of alternative culture. Film wise, the Philippines were the first third-world country I ever encountered. The smog was heavy, the traffic pure chaos, the climate suppressing. Nothing seemed to work properly. Improvisation was the order of the day and in retrospect I am inclined to believe this to be the true reason why experimental film is so wholeheartedly embraced - improvisation and experiment being close relatives. Still, people were patient and of a pleasant disposition. Virginia Moreno, then Director of the Film Centre at UP Manila, tried hard to make me welcome, even conducting a Sampangita tree-planting ceremony in my honour. She was a towering personality though physically of rather petite stature. To her minders she was extremely strict, bordering on harshness. Her status was based on rank, not material riches. The only apparent luxury was a car with a chauffeur. But a car so old the chauffeur constantly had to fix it to keep it running. Definitely in collision with all regulations of working hours he was at her personal disposal all hours of day and night. And he was used as a token of friendship. I remember vividly when Moreno sent me out into the Manila night-life with Nick Deocampo, her second-in-command. The chauffeur slept in the car when we woke him at 4 am to drive me home all the long distance from Ermita to Quezon City where I was based near the university. But despite all justified criticism of her behaviour she was respected an authority. This loyalty to the utmost to me was one of the most striking features of Philippine society.

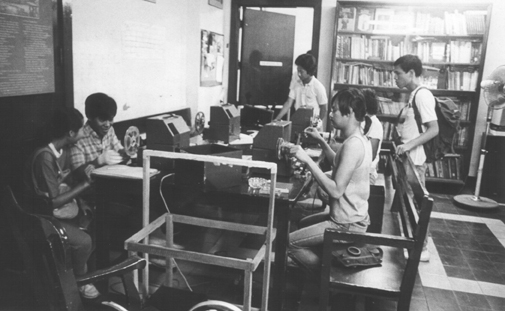

Beyond formalities and diplomacy, Nick Deocampo was the driving force of the independent short film scene. A dedicated filmmaker himself – everybody seemed in awe of his doco Oliver about a Spiderman impersonator – he was an academic who had written the first-ever book about Philippine short film history. Likewise he was a highly talented organiser. This became immediately apparent once the workshops were relocated from UP Manila to the Mowelfund Film Institute. This was a kind of self-governing structure which was run by Nick. Or so it seemed. I remember having the - doubtful - honour to be introduced there to an up-and-coming Philippine president whose major reason for fame was the fact that he openly had nine mistresses. Or maybe just seven, I don’t really recall. Nick and I got along well and were on friendly terms once it became clear we both shared a passion for film experiments but had quite different intentions in Manila’s burgeoning night life. I loved to take the ride to Ermita with him, though, encountering his growing enthusiasm for the ‘sisters of the night’. But once arrived we would split up and only meet again in the wee hours of the morning. He liked to chat and I loved his gossip about foreign filmmakers in Manila. Later I was able to help him with a few screenings in Europe but I still feel certain sadness that we lost contact along the way. The concept of experimental film fell on fruitful ground in Manila. My credo had always been that nobody could hope to successfully compete with Hollywood on Hollywoods own turf because their resources could simply not be beaten. Instead, it was not a bad idea to tell one’s own stories in ways based on ones own cultural background. In this respect, the experimental film was the perfect choice of genre with its inherent freedom of expression and flexible form. With its extremely low shooting ratio and its no-budget character, experimental film war particularly suitable for countries with a less-developed film industry and artists living in poorer conditions than in industrialised countries. The Goethe Institut had sent out filmmakers before but they had been into documentaries, particularly interested in street children, prostitution or the famous Smokey Mountain garbage dump. And here I came, screening Richter and Ruttmann, Nekes and Wyborny. The enthusiastic reaction to the films among the audience at UP Manila could virtually be felt. Gerrit Bretzler immediately responded by announcing a practical Super-8 workshop for the next year which I conducted as well. We brought in the film stock from Germany but for processing they had to be flown out to Australia as Kodak had just stopped doing this locally. The results looked a bit bumpy but definitely worth another try which was to be done in 16mm.

If I remember correctly, this was the first workshop at Mowelfund, a much more pleasant location in a more urban area. And it was the first to be conducted three-fold: one week or so concept and pre-production, then a break for me while shooting was going on, and then another week postproduction. I can still feel the thrill when for the first time we watched the “rushes”. Formal experiment was almost always tied to a political and/or social content – probably a reflection of the Philippine situation. Vicky Donato and Luis Quirino stick out as names. But the one film I will never forget was Jimbo Albano’s: for several days he had walked the tumultuous EDSA ring road, completely encircling Manila to come up with a marvel of structural film in single-frame shooting. There were more workshops to come but inevitably they got less exciting for me. The technical instructions would always be needed but I felt conceptual input, different thinking from other film makers was needed. And that was the way it went which was good. For me personally, the Philippines became more and more interesting, and the breaks in my work between pre and post turned into a major attraction. Twice I visited Pagsanjan, the location for the finale of Apocalypse Now!, my all-time favourite film. There I learned about the devastation Coppola’s crew had brought about – something to this day never related in any of the many books about him and the film. I experienced the beauty of Boracay when it was still a sleepy hollow of an island - omelettes with magic mushrooms on the menue. I even ventured all the way down south to magical-sounding Zamboanga – a place of political resistance to the Marcos regime, fed from many different sources. I still harbour fond memories of the weeks after the People Power Revolution with so much enthusiasm in the air. And I am still proud that eventually I was able to travel virtually everywhere in Manila by Jeepney, the way the locals do. Not even the taxi drivers could cheat on me any longer with their manipulated meters. I had arrived. Over the years, some of the film makers made it to Europe for screenings - with or without my help: Nick Deocampo, Luis Quirino, Cynthia Estrada. And it always felt good to get together again. But despite several attempts and offers of free study places, no prospective film student ever made it to my university. This feels sad but in all likelihood is due to non-existing funds on the Philippine side to cover some of the expenses involved. Today, my students will find a framed document on my office wall: the Independent Film Award for International Contribution to Philippine Independent Cinema. This was handed to me in a ceremony in 1986 – just after the revolution - by Deputy Secretary of the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport, Dr. Victor M. Ordoñez (thanks to Nick and Teddy!). A piece of paper and a haze of memories is all there’s left. But enough to once in a while remember a time to be proud about.

|